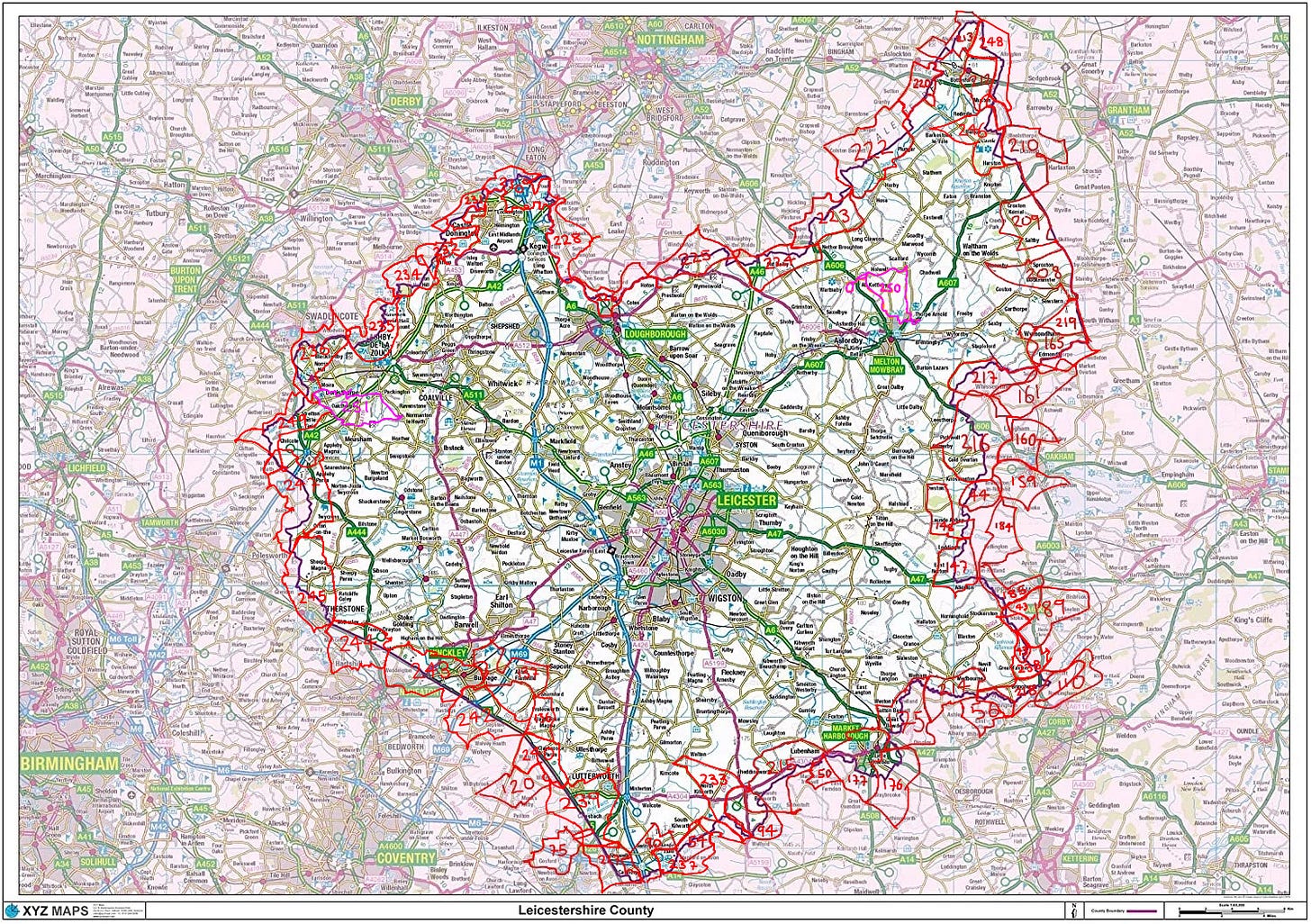

Earlier this month I completed my walk round the Leicestershire border. I’ve already summarised it on Twitter, and in this post I describe in more detail how I did it, what I found, and (in part 2) some reflections on what I learnt.

Background

I came up with the idea of walking the border in 2020, when (interrupted by the pandemic lockdown) I walked the Leicestershire Round, a footpath of a little over 100 miles that goes round the middle of the county, roughly in an oval shape. It touches its eastern and western borders but not those to the north or south; it goes some way south of the towns in the north of the county, Melton Mowbray, Loughborough and Ashby, and it is well north of Lutterworth. So, much as I enjoyed the Leicestershire Round - it gave me a sense of how the county fits together, and in particular the differences between the fairly crowded west and the much sparser east - I decided that walking the actual border would be an interesting future challenge.

When I got to that challenge, in early 2022 (having in the meantime completed the Rutland and Northamptonshire Rounds), I realised there were two particular issues I would face. The first was that it is impossible for much of its route to walk the border itself. There is a twenty-mile section at the southern end of the western border where it follows the A5, so I could have walked the littered verges and braved the HGV fumes, though I chose not to. At the opposite end of the county, part of the border with Lincolnshire follows a quiet country road, which was a much nicer experience.

But for most of its length, the border either goes across farmland or follows the course of waterways that are not always easy to access. These range from the mighty Trent, the Soar that soars north towards it from Loughborough, and the Avon that is small here but later goes through Stratford to the Severn; to a poetic selection of streams given brief importance by their responsibility for marking the border as they splash along: the Welland, Gwash, Smite, Mease, Anker and Devon Rivers; the Dingley, Eye, Somerby, Dalby, Whissendine, Kingston and Hooborough Brooks; and the Winter and Rundle Becks. The border also, not coincidentally, winds through the Eye Brook, Stanford, Welford and Staunton Harold reservoirs, which mostly nestle discreetly between the gently rolling hills that make up this part of the world.

So I decided to walk round or parallel with those sections of the border I could not walk along, so as to encompass the border section by section. (In fact I tightened up the rules I had set myself part-way through, and redid a couple of legs in the north-east of the county, walking round sections which I had originally walked parallel to but some distance from). There were a few small, winding corners of the border that I could not easily find a route round; but the only substantial section I did not encompass was where the border follows the Trent and has no crossing for some distance. Rather than swim across, I walked each side of the river in turn and waved at where I had been. That had to do.

The other issue was that I’d already inadvertently encompassed parts of the border on previous walks, sometimes several years earlier, though in most cases only small sections at a time. After some rather tedious detective work, I established that fourteen of my previous walks (including a couple of legs of the Leicestershire Round and one of the Rutland Round) had covered much of the southern border and the southern part of the eastern border. I then had to plan a further eight walks to fill in the gaps between those. That is why there are 14 (randomly and inefficiently-shaped) legs covering the southern border, while the northern border, of a similar length, only took nine.

It also helps explain why the total distance I walked, some 645 miles, was well over three times the actual length of the border (which is about 200 miles, enclosing a county that is over a third as big again as Greater London). On top of the previous fourteen walks, and the eight to fill the gaps between them, I did another thirty legs to complete the border, so 52 in total. The 30 dedicated routes were each planned to cover as much of the border as possible, given the limits of public footpaths and of my actual legs. The longest individual walk I did was well over 17 miles.

The western border

I will start the border’s story in the bottom left-hand corner of Leicestershire and go clockwise. Here we find the village of Catthorpe, uncomfortably squeezed between main roads: the M1 thunders to its east, while the M6, the longest motorway in the UK, starts its journey here, to go through Birmingham and ultimately end (as the M74) in Glasgow. The A14 heads off in the opposite direction, east to Cambridge and eventually to Felixtowe, which explains why it is such a favourite with the lorries. Both the M6 and the A14, though launched in Leicestershire, are quickly handed over to other counties to nurture. Meanwhile the A5 seems to operate in a parallel dimension, sidling under the M6 and refusing to engage with any of the other main roads nearby; it eventually meets the M1 in Northamptonshire, not far from the famous Watford Gap service station.

A little south of Catthorpe is the southernmost point of Leicestershire, at a bend of the River Avon - like all of Leicestershire’s extremities it is near a tripoint (where three counties meet), in this case a few hundred metres from where Northamptonshire (to the south) and Warwickshire (to the west) touch Leicestershire. This tripoint, to the west of Catthorpe, is where the western border starts, as it leaves the Avon and starts tracking the A5 northwards.

As is well known, the A5 began life as Roman Watling Street, which starts in distant Kent, travels through London (as the Edgware Road), and ends up at the village of Wroxeter in Shropshire, seventy miles west of Leicester and the site of the fourth largest city in Roman Britain. The border follows the A5 for some twenty miles north-west, going under the M69 motorway and bisecting the towns of Hinckley and Nuneaton, almost to Atherstone (where there is a chaotic medieval football match each Shrove Tuesday). Unlike the rest of the border, which mostly meanders, here it is as straight as you would expect of a Roman road.

At High Cross, Watling Street met Fosse Way, the junction of the two most important Roman Roads in Britain. This was the site of a Roman fort, Venonis, and later a medieval gibbet. Only the plinth now remains of an early eighteenth century memorial marking this as the centre of Roman Britain - it doubled up as a celebration of recent military victories against France. It was struck by lightning in 1791.

North-west of High Cross, at Lindley Hall Farm, is the actual centre of modern England, as calculated by the Ordnance Survey. A marker shows the spot, but is on private farmland and inaccessible.

Watling Street, like other Roman Roads, continued to be important well after the Romans left: for centuries, what is now the Leicestershire-Warwickshire border was in practice part of the boundary between Anglo-Saxon and Viking rule, and even by the eleventh century, when England was broadly unified, it marked the south-west edge of the Danelaw. As a result, there are plenty of settlements with Scandinavian place-names on the Leicestershire side of the border (such as Ullesthorpe, the settlement of a man called Ulfr), but fewer on the Warwickshire side. Similarly, the Domesday Book of 1086 records many more freemen north-east of this border.

The A5 section was not the most pleasant part of the walk, through the industrial estates of Lutterworth and the suburbs of Nuneaton, but I walked part of the Ashby-de-la-Zouch Canal west of Hinckley in the late afternoon sun in early February and enjoyed the still colours in the pale winter light.

Just south of Atherstone, the border finally leaves the A5 and meanders northwards past Twycross Zoo and under the M42. A few miles east of here is Bosworth Battlefield, where Richard III lost his life and his crown, and the Tudor dynasty was founded.

North of the oddly-named No Man’s Heath is Leicestershire’s short (half mile or so) border with Staffordshire, at the northern end of which - at an undistinguished bend in a river at the bottom of a field near a solar park - is the westernmost point of the county. It is further west than both Coventry to the south and Derby to the north.

(This half-mile border is, as an aside, extravagantly long compared to the one between Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire - two counties that border Leicestershire, but which themselves meet on the other side of Rutland at the shortest county boundary in England: it is only about 20 metres long, which means Rutland and Peterborough [Cambridgeshire] at either end of it are close but can never meet. That scene is at the edge of a field by the A1 south-west of Stamford. I have been there, of course, and can confirm there is nothing to see.)

North of that bend in the river, the border (now with Derbyshire) heads north-east past the villages of Netherseal and Overseal. These were given to Derbyshire at the end of the nineteenth century in return for various exclaves, including nearby Chilcote and Donisthorpe, being made part of Leicestershire (this also sorted out the counter-exclaves - that is, pieces of Leicestershire within the pieces of Derbyshire within Leicestershire).

The border travels through the outskirts of the Derbyshire former mining town of Swadlincote, the only point at which it goes through a built-up area and divides communities in two, including the appropriately-named hamlet of Boundary. It passes Ashby-de-la-Zouch then goes up past Calke Abbey, where I captured some glorious autumn sunsets, and near the Iron Age Hillfort at Breedon on the Hill.

Leicestershire has two large “triangles” sticking up from its northern edge. We are now at the smaller one, to the north-west, which divides Derbyshire to the west from Nottinghamshire to the east. The border continues north-east, passing the Donington Park racetrack and East Midlands Airport, then joins the Trent, which it follows all the way to the top of the triangle - the thin end of the wedge, as it were.

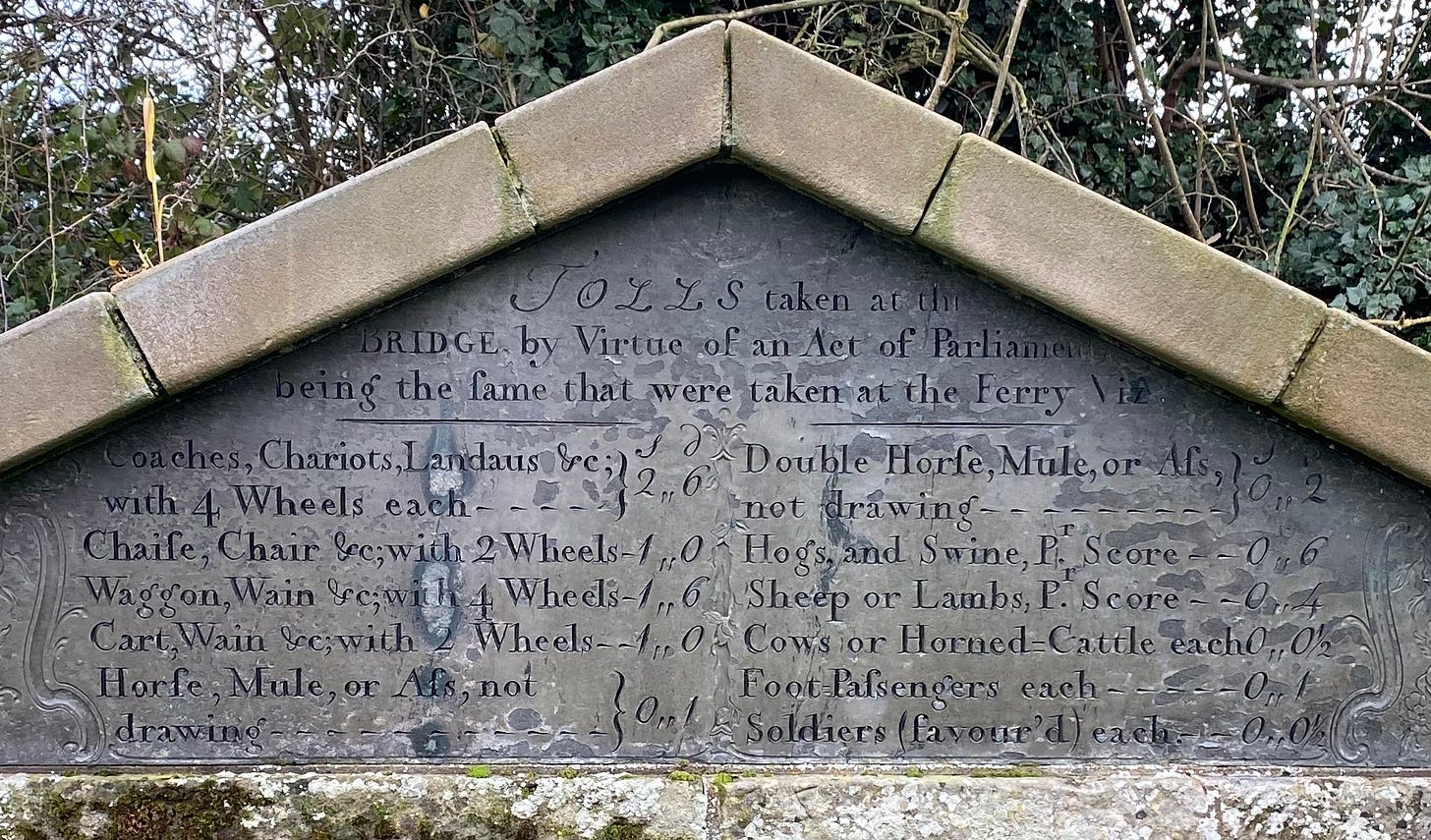

It goes with the river under what used to be a toll bridge at Cavendish Bridge, which has a stone plaque on the north bank setting out the detailed charges as required by an Act of Parliament, which were levied until 1888. It also passes under the M1, which has taken a shortcut here from Catthorpe, skirting the western edge of Leicester.

The northern border

The tripoint where Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Leicestershire meet is in the middle of a river junction just south of Long Eaton, where the River Soar joins the Trent, by a railway bridge I have been over many times. One of the joys of walks like this is having the time to look properly at views you see only fleetingly from a car or train.

The Leicestershire-Nottinghamshire border then heads south down the River Soar towards Loughborough. The landscape here is dominated by the cooling towers of the Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station, one of only two coal-fired power stations left in the UK, which is due to close next year. East Midlands Parkway railway station sits at the feet of the power station. I started this leg of the border from the station last October, and live-tweeted it. Going down the Soar, the border passes East Midlands Airport again to the west, as aeroplanes descend overhead.

Just north of Loughborough, the second biggest town in Leicestershire, the border turns east and then eventually north-east, up the side of the second “triangle”, to the north-east of the county, which divides Nottinghamshire from Lincolnshire. Leicestershire’s northern border is rural - I walked it last summer, and remember hot, hazy days walking by canals and through fields.

Stilton cheese can only be made in this part of the world (even though Stilton itself is in Cambridgeshire): I walked past one of the dairies allowed to make it, at Long Clawson. I also passed the sad remains of cricketer Stuart Broad’s Tap and Run pub in Upper Broughton, which had burnt down a few weeks before.

And we shall complete the journey in part 2. Click subscribe to make sure you get that.