This series (part 1 is here) started as a collation of stories about Leicestershire’s villages and towns, but as I’ve followed long threads of curiosity to put those stories into context, it’s turned into something rather more than that. I am finding it fascinating and intriguing to research and write, and I hope readers equally enjoy reading and perhaps learning something from it.

The Wars of the Roses

The Battle of Bosworth Field, the decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, was fought in west Leicestershire in August 1485 between Richard III and the rebel Henry Tudor. It was one of the most consequential battles ever fought on English soil, not only historically but also culturally1. It is easy to overlook that the outcome was no foregone conclusion, partly because there were more than the normal two armies involved: the rebel force faced a Royal army more than twice its size, until the scheming Lord Thomas Stanley, who (with his brother Sir William) had been watching the battle, led his army to intervene on Henry - his stepson’s - side, despite Richard having taken the precaution of holding Stanley’s son hostage in order to try and secure his support2; and then Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, failed to bring his men to the King’s aid, a decision which helped to seal Richard’s fate3.

So it is quite plausible that Henry could have been defeated and killed in the battle, and English history would then have unfolded quite differently. The Wars of the Roses (as they were not known at the time) may have continued, and Richard might have been overthrown eventually, but it is unlikely it would have been the Tudors who usurped him4, so there would have been no Henry VIII (who was not born until six years after Bosworth) or Elizabeth I. England may well have ended up as a Protestant nation eventually, given the religious turmoil in Europe over the next hundred years, but surely no alternative dynasty would have overseen an English Reformation in the idiosyncratic way the Tudors did.

The abbeys of the twelfth century could therefore still be standing today (as it was, all the Leicestershire abbeys discussed in part 1, including Leicester, Launde, Owston and Croxton, were dissolved by Henry VIII fifty years after Bosworth). Maybe the English and Scottish crowns would have been united in the early seventeenth century, and a Civil War fought by a King against Parliamentary forces a few decades later, but it seems more likely that England and Scotland would have made their uncertain way towards the Industrial Revolution and Parliamentary democracy down quite a different path.

And had the Stanleys and Northumberland made alternative choices in the heat of battle that August day, our cultural life would have been markedly changed too: no Wolf Hall, no Blackadder the Second, and no Six. Shakespeare’s milieu and some of his historical plays would have been different (maybe Richard III would have been a hero?) Bosworth Field would probably be thought of today as one in a long line of bloody but obscure fifteenth century battles in which an attempt to overthrow a king had failed. Henry Tudor’s body might have been found underneath a Leicester carpark in 2012, though such a discovery would surely not have captured the imagination of the world; and maybe there would never have been a carpark anyway, as the Greyfriars Priory could well still be there (on our timeline it too was dissolved in the sixteenth century), a striking addition to the central Leicester skyline we know. It might have had a little-noticed gravestone in the choir of its Friary church as a reminder of an almost-forgotten Tudor noble.

There had also been a Leicestershire connection right back at the start of the Wars of the Roses, forty years before Bosworth, in 1455. The first battle was at St Albans, down Watling Street from Leicestershire, after the ineffectual Henry VI (1421-71)5 had called a Great Council at Leicester, which Richard, Duke of York6 and his fellow Yorkists did not want to happen. So they intercepted the King’s retinue - which was making its way to Leicester - at St Albans, where fighting broke out. Although the “battle” was little more than a skirmish through the streets of the town, it did result in the death of the Duke of Somerset, commander of the Royal army, which consolidated York’s position7 as a key adviser to the King.

Passing over years of bloodshed we arrive at the uneasy summer of 1483: the twelve-year-old Edward V had just succeeded his father, Edward IV8, as King9. Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV’s Queen and mother of the young King, had previously been married to Sir John Grey of Groby (1432-61), who was killed at a second Battle of St Albans while fighting for the Lancastrians.

William, Lord Hastings, who had been a close adviser and Lord Chamberlain to the new King’s father, was then in the process of building a magnificent brick castle at Kirby Muxloe. The Hastings family (later granted the Earldom of Huntingdon10) were stewards of Leicester, and were influential in the town for many generations. The castle, though, remains poignantly unfinished: Hastings was accused of treason and summarily executed by Edward V’s uncle, the Duke of York, following a Council meeting at the Tower of London in the middle of June11). Hastings had also been responsible for the eponymous tower at Ashby de la Zouch castle (qv).

Edward V did not last long: the Duke of York claimed the throne in late June and was crowned as Richard III at the beginning of July. Just weeks later he was in Leicester, signing letters ‘from my castle at Leicester’. Meanwhile Edward was sent to the Tower of London with his younger brother; Richard almost certainly had the two ‘Princes in the Tower’ killed12, either in the summer, when they disappeared, or later that year.

But Richard’s position was not secure: he had made enemies on the way to the throne, including the Woodvilles (aka Wydevilles) and the Duke of Buckingham, who was executed in the autumn of 1483 for leading the ‘Buckingham Rebellion’13. Over the following two years Richard’s opponents united behind Henry Tudor, who was exiled in Brittany and then France. In early August 1485 Henry led his forces across the Channel to Wales, landing at Milford Haven, and then marched to Leicestershire, heading eastwards towards the battlefield from Atherstone. Richard, having come down from his base in Nottingham, marched westwards from Leicester. They met on 22nd August.

Until 2009, the site of the Bosworth battlefield was contested, but we now know it was fought near Stoke Golding - the villagers there reputedly climbed the church to watch the fighting14. But other villages claim connections to the battle too: although the most common story is that Richard spent the night before the battle at the Blue Boar Inn in Leicester, both Stapleton and Dadlington claim he actually slept there. He is supposed to have heard his last mass at Sutton Cheney, and his officers were said to have stayed beforehand in the ruins of Elmesthorpe church (no doubt other claims are available). After the battle, the bodies of the fallen were brought to St James's Church in Dadlington for burial.

After Richard’s defeat and death from a blow to the head, his body was taken east to Leicester, publicly displayed for three days in the Church of the Annunciation, and then buried unceremoniously at Greyfriars Priory. Meanwhile, Henry was crowned as Henry VII15 at Stoke Golding with the coronet that had been worn by Richard. And so the Tudor era began (and the Middle Ages ended) in Leicestershire.

The Tudors

To strengthen his claim to the throne, Henry married Edward IV’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth. The Wars of the Roses did not end until Henry’s decisive victory at the Battle of Stoke Field in east Nottinghamshire in 1487, against a Yorkist attempt to try and secure the throne for the ten-year-old impostor Lambert Simnel (Henry’s route to that battle took him through Leicester and Loughborough). Even then, Henry’s position was not secure until the very end of his reign: in particular, in the 1490s another Yorkist pretender named Perkin Warbeck16, claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury (the younger of the Princes in the Tower), made several unsuccessful invasion attempts with the support of various European monarchs. By the end of his reign, however, Henry had improved England’s international standing and security through peace treaties and shrewd marriages17. Avoiding wars allowed him to strengthen England’s economy, and he oversaw effective and efficient administration, including tax collection.

Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort18, was highly ambitious for her son and a key influence in his ascent to the throne. Her fourth husband was Thomas Stanley, who had helped to determine the outcome at Bosworth. Margaret was also a major patron of academia and the arts, in in 1505 she refounded Christ’s College Cambridge and endowed it with (among other things) lands at Diseworth and Kegworth, which the college owned until it sold them in 1920.

Henry died in 1509 and was succeeded by his second (and only surviving) son, who became Henry VIII19. William Skeffington (c1465-1535), born in the village that shared his name, was with Henry at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, a grand summit meeting near Calais in 1520 between Henry and the French King, François I. Skeffington was later Lord Deputy of Ireland (the King’s representative). His son Leonard was Lieutenant of the Tower of London and invented the Scavenger’s Daughter, a particularly unpleasant torture rack.

William Wyggeston, or Wigston (c1467–1536), a wealthy wool merchant, was twice mayor of Leicester (his father, John, had also been mayor), was MP for Leicester in Henry VII’s last Parliament, and was also four times the mayor of the Staple of Calais20. He founded Wyggeston Hospital (almshouse) in 1513; the successor charity, south-west of the city centre, still provides sheltered housing for older people. After his death, Wyggeston’s money was used to found a grammar school, whose name lives on in Wyggeston and Queen Elizabeth I Sixth Form College. His is one of the four statues on the Clock Tower in Leicester city centre21.

Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, was arrested near York in November 1530 and accused of treason, having failed to secure an annulment of Henry’s first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon. He died of illness in Leicester on 29 November on his journey south to face trial, and was buried in the Leicester Abbey church, though his remains have never been found.

Thomas Cromwell (c1485-1540), Henry VIII’s Chief Minister who was responsible for the dissolution of the monasteries, spent time in Leicestershire towards the end of his life (he was executed in 1540): the King granted him the manor of Blaston and a priory in Melton Mowbray, where he briefly lived, which is now the Anne of Cleves pub (so-called because Anne, Henry’s fourth wife, received the building in her divorce settlement following Cromwell’s execution, though it is not known whether she ever visited)22.

Cromwell visited Launde Abbey, near Loddington (qv), shortly before his death and, being very taken with it, began the process of converting it from an abbey into a country house; and though he never got to live there, his son Gregory (c1520-51) spent many years there with his wife Elizabeth Seymour (c1518-68), sister of Henry VIII’s third wife Jane. Gregory died and was buried at Launde.

Henry VIII died in 1547 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son by Jane Seymour, who became Edward VI. But after just six years on the throne, Edward - a committed Protestant - died of tuberculosis at the age of 15. He was briefly succeeded by Lady Jane Grey (1537-54)23, thanks to the ambitions of her fiercely Protestant father-in-law, John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland - she had no say in the matter. Jane, also a Protestant, had been born at Bradgate House, a red-brick Tudor mansion near Newtown Linford (whose ruins can still be seen in Bradgate Park). At the time Jane was Queen her father, Henry Grey, was lord of the manor at Great Glen.

Jane was famously Queen for just nine days in July 1553, which she spent in the Tower of London, before being usurped by Mary Tudor24, the only surviving child from Henry VIII’s first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon. Northumberland was quickly executed at Tower Hill. The Tower of London then became a prison rather than a palace for Jane and her young husband, Guildford Dudley25. It looked as if she might be pardoned, as Mary had sympathy for her, until her family took part in a rebellion later that year, and Jane then refused to convert to Catholicism. So she and her husband were both beheaded in February 1554, Jane famously showing great courage on the scaffold26 (it is said that the oak trees at Bradgate Park were ‘pollarded’ - the tree equivalent of being beheaded - at the news of her execution).

As a Catholic, Mary restored papal supremacy in England, abandoned the title of Supreme Head of the Church and reintroduced Roman Catholic bishops. She also revived the old heresy laws, and hundreds of Protestant ‘heretics’ were killed27. They included Bishop Hugh Latimer (c1485-1555), born in Thurcaston, a Protestant preacher and Bishop of Worcester, who was one of the ‘Oxford Martyrs’, burnt at the stake in what is now Broad Street in central Oxford. In June 1556 a 24-year old servant named Thomas Moor was burnt at the stake in Leicester.

Mary was Queen for just five years before she died, possibly from cancer, at the age of 42; she was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth, daugher of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife, and the third of his children to take the throne. Elizabeth never visited Leicester, though on several occasions there were plans for her to do so, for which the town made expensive preparations. However, she had a close relationship for most of her life with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and she gave the town a charter in 1589, which established the Corporation; the town took her motto, Semper Eadem (‘always the same’).

The church at Nailstone has a monument to Thomas Corbett, Sergeant of the Pantry to four Tudor monarchs, who had twenty-one children and died (in 1586) aged 94.

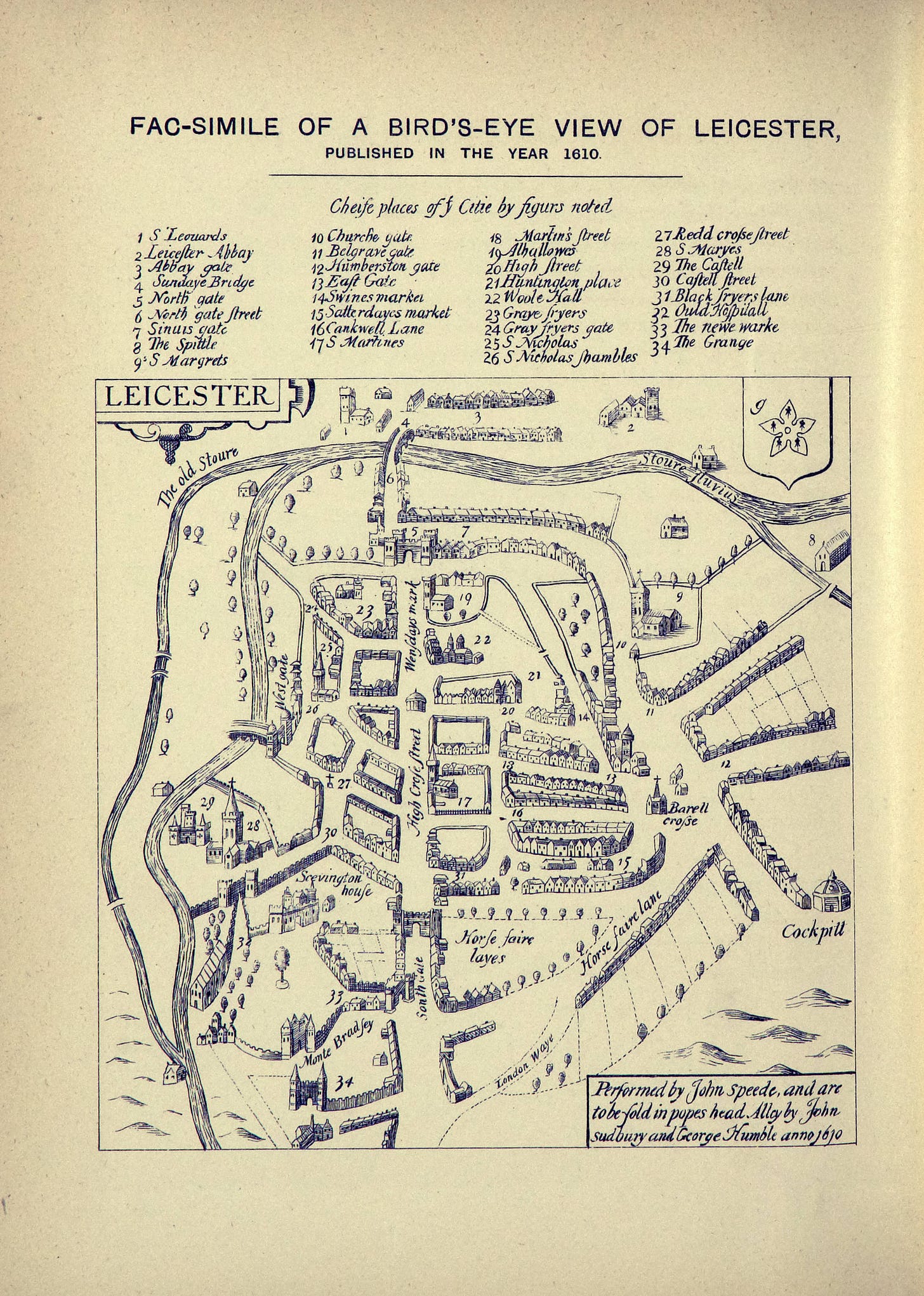

Leicester around 1600

Leicester had lost its city status in the Middle Ages28, and did not regain it until the twentieth century - hence it is referred to at the end of Shakespeare’s Richard III as ‘Leicester town’29. Its population at the end of the sixteenth century was around 3,500 (up from 1,500-2,000 at the time of the Domesday Book, but less than 1% of its current population).

Ten years after the first charter, the town was issued with a new Royal charter in 1599, under which it was governed by a Mayor, 24 aldermen and 48 other councillors, who between them took on a wide range of duties (some of which are familiar, while others would seem strange today)30. The Mayor was expected to dress in scarlet on holidays and fair days, and aldermen and councillors had to wear caps and gowns at official functions. The aldermen were elected from the council members, and the councillors from the freemen of the town (who acquired freedom by birth, serving as an apprentice, or by giving money or a bottle of wine to the Corporation) - freedom of the borough was needed before someone could set up a shop. In the early sixteenth century merchants (who were often also landlords) dominated the Corporation, though later craftsmen and producers had some influence.

Two Chamberlains, chosen from among the alderman and councillors, were responsible for the town’s finances; they carried staves and had to hold an annual dinner. Five sergeants-at-mace were responsible, among other things, for making proclamations and arrests and (as the name suggests) carrying the town’s maces; they were provided with gowns and got a fee for every prisoner committed.

William Skeffington’s (qv) great-grandson Thomas Skeffington (1550-1600) was Sheriff of Leicestershire, and built Skeffington House, now part of the Newarke Houses museum31. According to Nichols, in 1588 in response to the threat of the Spanish Armada, Thomas ‘summoned together all persons [in Leicestershire] between the age of 18 and 50 years (to the number of 12,530) able to bear arms; 2,000 of the prime of which were sent to Tilbury camp32, the rest were sent home furnished with various missile weapons, and directed to rendezvous on the first news of the Spaniards setting foot on English ground’33. Towns had to organise the training and equipping of soldiers to contribute to the country’s defence, in the form of ‘trained bands’; Leicester kept a stock of armour, ammunition, and weapons, and in 1607 employed a town armourer.

Other officers of the town included stewards of the fair (in 1540, Leicester had been granted two additional annual fairs, for five days each in June and December, in addition to the medieval fairs held in May and September) as well as fish34, meat and leather testers, a librarian and a beadle. Justices of the Peace were drawn from the mayor and aldermen, and were responsible for overseeing the poor law; the town provided a cucking stool and stocks for the punishment of offenders. The town’s recorder - senior legal officer - was a prestigious role, and was typically occupied part-time by an eminent London-based lawyer. John Beaumont (c1508-c1564), who was born in Belton, was appointed Leicester’s recorder in 1550, and in the same year became Master of the Rolls, a post that had recently been held by Thomas Cromwell35.

An 'Acte for Nyght Walkers' in 1553 set penalties for being out of doors after 9pm, and a special watch was kept on alehouses, lodgers, strangers, and people with the plague36. The ten wards of the town were each overseen by an alderman. Regulations were made for the disposal of dung, and aldermen had to keep leather buckets in case of fire - buckets and hooks were also kept at each of the town’s gates. The Corporation was required to keep a uniform set of weights and measures, which were kept in the town hall and checked periodically (in 1578 they were found to be faulty).

The Corporation spent the first few decades of the seventeenth century trying to get a new charter which would give it more control of lands outside the town walls, such as the Newarke (which, it was alleged, harboured unlicensed alehouses and nonconformists) and the Bishop’s Fee (owned by the Bishop of Lincoln), but these attempts were resisted by local landowners, in part to avoid giving the Corporation the power to regulate and reduce the freedoms of craftsmen (their tenants) outside the town’s walls37.

There are many records of commercial activities in the town, providing insights into daily life. For example, mercers originally sold cloth, but by the seventeenth century had broadened their wares to cover groceries, haberdashery and linens too38. Leicester had about nine mercers, who typically bought goods wholesale in London and Manchester and sold them in shops and market stalls in Leicester, and sometimes in other parts of the county as well. They used common carriers, which provided a regular service transporting people and goods long distances by horse and cart, including to and from London.

One mercer, Richard Hilton, who died in 1574, sold goods including canvas, herefords, minsters, ghentish, carrel, mockado, russets, sackcloth, points, silks, cards, gloves, lace, thread, girdles, paper, brushes, leather laces, pins, cotton wool, pepper, saffron, cloves, nutmeg, almonds, rice, aniseed, brimstone, starch, sugar, prunes, treacle, currants, liquorice, and other commodities. Another, Nathaniel Brokesby, sold (among other things) silks, silver lace, silk and cotton ribbons, buttons, taffety, tabby, calico, canvas, dimity, buckram, tobacco, flax, soap, oil, leather, and coloured skins39.

Trade was tightly regulated: guilds and companies, along with the Corporation, sought to restrict competition (particularly from people outside the town), manage the status of different trades, control employment of apprentices40 and children, and in some cases enforce monopolies. Even the leisure hours of servants were regulated and supervised. Jersey spinning and knitting were taught to children and people needing poor relief.

The Assize of Bread and Ale (see part 1), which regulated quality, price and size, was still in force (and remained so until the nineteenth century). In Leicester there was the added complication that the Duchy of Lancaster (which had a lot of property and therefore power in the town41) owned several common ovens and mills, and tried to prevent people using any alternatives. In the seventeenth century, there were six common Duchy ovens in the town, which most people in Leicester used to bake their own bread, but there were regular attempts to allow alternative ovens to be used in the name of free trade. The Duchy Court regularly heard cases involving ‘unlawful’ bread, as well as pies and cakes.

There were similar problems with beer and ale - the aldermen of the ten wards acted as ale testers unless they were themselves brewers - with rows over the regulation of malting and brewing, both of which required expensive equipment. Some people brewed for their own consumption, but brewing and innkeeping were both good sources of income - there were about 160 alehouses42 in seventeenth century Leicester, some of which had skittle alleys.

Even in the town, agriculture dominated life: pigs and cows were herded in the streets, and there were fields all round the town walls, mostly held in common. Many townspeople kept animals or grew crops, and lots of families had dairies. For some, agriculture was a part-time occupation alongside other trades, though there were large farms too: farmers were the largest employers of labour in Leicester and most wage-labour was agricultural.

Other professions in the town included apothecaries, barbers, physicians, lawyers, scriveners (who wrote documents), gardeners, gaolers, schoolmasters, priests, musicians and a postmaster.

In part 3, we will reach the seventeenth century, which brought new turbulence for England in general and Leicestershire in particular. Do subscribe to make sure you get that.

And it was the last battle in which an English king was killed.

Stanley got a message from Richard before the battle threatening to kill his son if he did not come to the king’s aide, to which he responded with the heartless ‘Sire, I have other sons’. Despite this, the son - George, Lord Strange - survived.

Many of the online accounts of the battle are confused and confusing (one confidently asserts it took place in Warwickshire), but this paper produced by English Heritage in 1995 is comprehensive and clear in its discussion of the surprisingly slight documentary evidence about what actually happened (though it is now out of date in its description of the controversy around the location of the battle).

The Tudor claim to the throne was not strong.

Henry VI was the great-grandson of John of Gaunt (see part 1).

The Duke of York was the future Richard III’s father, who had been knighted at St Mary de Castro church in Leicester in 1426 alongside the young Henry VI (see Part 1).

Though not for long, as evidenced by another 40 years of complex, intermittent dynastic fighting.

Edward IV had, in the meantime, alternated the throne with Henry VI in a kind of Royal hokey-cokey.

There are lots of King Edwards in this story.

The third Earl, Henry, was Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire in the second half of the sixteenth century, and acted as gaoler for Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-87) when she was briefly held at Ashby de la Zouch castle in 1569.

Hastings is a character in the Shakespeare plays Henry VI part 3 and Richard III; his role is discussed in the Rest is History podcast episode on the Princes in the Tower.

No thank you, I don’t want to debate this.

The 1483 rebellion was seemingly seen off in part due to storms and floods.

The battlefield was a little to the south-west of Ambion Hill, previously assumed to be its location, which is where the Bosworth Battlefield Heritage Centre is.

Henry VII was the fourth Henry to reign in the fifteenth century, the only time four different English monarchs with the same name have ruled in one century. An additional piece of monarchical trivia: the only three fifteenth century monarchs not called Henry were all on the throne at some point in 1483.

Fifteenth century pretenders tended to sound like characters from Roald Dahl books.

Including Catherine of Aragon, who married Henry’s elder son Arthur, and then after Arthur’s death in 1502 his second son Henry. Henry VII’s daughter Mary married the Archduke Charles, later Emperor Charles V.

My college, Lady Margaret Hall, was named after her, which triggered my long fascination with Margaret (who was only 13 when Henry was born, and had no other children).

A recent YouGov poll found Henry VIII to be Britons’ least popular English monarch.

A Staple was a place where wool could be traded, a system set up by Edward III in the fourteenth century; Leicester itself became a Staple in the early seventeenth century.

The other three statues - all men - are of Simon de Montfort (see part 1), Sir Thomas White (1492-1567) who in 1542 established a fund to support the establishment of new businesses (which still exists), and Alderman Gabriel Newton (1683-1762), whose legacy was used to establish the school where the King Richard III visitor centre is now based, and whose educational foundation also still exists).

More generally, according to the Discover Melton website, ‘from the late 1100s onwards, the Great North Road from London to York and Edinburgh was diverted through Melton Mowbray and so contributed significantly to Melton’s early prosperity…during that period, eleven Kings of England visited Melton Mowbray’. I have no reason to doubt this, though I have not been able to verify it.

Jane was great-great-granddaughter of Sir John Grey (qv) and great-granddaughter of Henry VII.

The Rest is History podcast episode on Lady Jane Grey is worth a listen.

Guildford was the younger brother of Robert Dudley, who went on to become the first Earl of Leicester and favourite of Elizabeth I.

Paul Delaroche’s painting The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, painted in 1833, is in the National Gallery.

Which explains why she was called Bloody Mary by her Protestant opponents.

I haven’t been able to find any details of why or when this happened. If anyone has any details, do let me know.

There is also a reference to Leicester in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, and to Leicestershire in Henry VI part 3. Hinckley Fair gets a mention in Henry IV.

This section draws heavily on Victoria County History (VCH) work on the City of Leicester (accessed February 2025): 'The City of Leicester: Social and economic history, 1506-1660' and 'The City of Leicester: Political and administrative history, 1509-1660', both in A History of the County of Leicester: Volume 4, the City of Leicester, ed. R A McKinley (London, 1958).

The other of the Newarke Houses is the Chantry House built by William Wyggeston (qv).

The English army was gathering at West Tilbury, on the Thames east of London, where Elizabeth I gave her famous speech.

The eating of fish on fast days was enforced.

But Beaumont’s legal career came to an abrupt end after he was imprisoned for corruption.

Plagues, famines and harvest crises were regular occurrences in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

VCH has plenty of detail about the endless and sometimes quite petty disputes between the Corporation of Leicester and others, including the Duchy of Lancaster, the county authorities, church institutions and other landowners.

VCH also has examples of (among other things) stationers, ironmongers, vintners, pedlars, shoemakers, tanners, glovers, weavers, bonelacemakers, ropers, carpenters, upholsterers, joiners, wheel-wrights, butchers, bakers and candle-makers. Many people combined trades (for example, blacksmiths often spun or farmed, one bellfounder was also a tanner, and glaziers were often plumbers, perhaps because both worked with lead).

Ibid. I have no idea what some of these things are.

Apprenticeships were regulated by the Statute of Artificers of 1563, which (among other things) made seven-year apprenticeships compulsory for some trades, and required magistrates to set agricultural wage rates. It remained in force until 1813.

The Monarch has been the Duke of Lancaster since the end of the fourteenth century, but the Duchy estate is kept separate from the rest of the Crown’s possessions. The Reeve Piece in Desford is the Duchy’s longest-owned piece of land (see part 1).

Do the maths: if that figure is true it’s a huge number for a town that size.