A few months ago I posted a music ‘hack’ - a list of pieces of music I like which others may enjoy exploring (‘hack’ in the sense of a short-cut, like a life-hack - I hope it would be an easy way for readers to discover new music).

The twist was that all the music was by women, from the C12th abbess Hildegard of Bingen to Anna Þorvaldsdóttir (b 1977). I got some positive reactions to it. So here’s a second hack: recommendations and personal reactions to twelve pieces by twelve different composers (from the C17th to the present day) that readers may not have come across before. Unlike last time, I’ve allowed music by male composers.

As before, this music has nothing in common except that I like it, and that it is not particularly well known, but which the listener with open ears may find an unexpected pleasure. Some of this music is not particularly easy to listen to and may need a few goes to appreciate, but I would encourage listeners to persevere. Although the music covers different eras and styles, as I re-read my listening notes I find some of the same words recurring, which perhaps tells you something about the music I enjoy… Anyway, I hope you do too.

I have provided Spotify links to make the music easy to sample, but if you like it please consider paying for it.

CPE Bach (1714-1788): Cello Concerto in A (1750).

CPE was the fifth child of the great JS Bach and his first wife Maria Barbara, and he bridged the gap between his father’s baroque style and the classical style of Haydn and Mozart. The piece opens with a lively characterful dance, and when the cello enters it duets with the upper strings, low in its register, almost a moto perpetuo (fast and constantly moving) as it runs up and down scales. The continuo accompaniment beneath gives it a slightly clattery feel, which for me adds to the sense of excitement. A brief three-note legato descending phrase keeps coming back, for a bit of tonal contrast - the rest is quite staccato (short, separated notes). The second movement sighs deeply, and the cello, when it comes in, sings with a quiet, pinched intensity. The mood is one of agonised desolation, lasting a full eight minutes. The finale I know well from the cover disc of an early issue of the long-defunct Classic CD magazine. Like the first movement it dances energetically down and up after opening with a flourished chord. Regular outbursts are followed by a pause, and the music creeps away briefly. Fast, rich arpeggios (broken chords) in the cello are interspersed with moments of climbing intensity. It stops abruptly, exhausted, but that tune keeps dancing round my head for a good while after.

Heinrich Biber (1644-1704): Missa Salisburgensis (1682).

This vast edifice of a piece, a monumental combination of baroque drama and power, was written to mark the 1,100th anniversary of the founding by St Rupert of the Archbishopric of Salzburg. It aims to make the most of the space and acoustics: it comprises many different groups of singers and instrumentalists who would have been spread around Salzburg’s large Cathedral. It opens with raucous trumpets and drums playing great echoing fanfares (this recording was actually made in Romsey Abbey). Then the Kyrie starts with a sheer wall of choral and organ sound, immense in its grandeur. It constantly seems like the soloists are going to get overwhelmed, but the struggle to be heard is part of the point, and similarly with the occasional violin solo that peeps out. The grunts in the lower brass are gorgeously fruity. It is both dramatic and evocative. To my ears, there is nothing particularly innovative about it musically - it’s all about the sound, and relishing the sheer, unashamed joy of celebratory noise (I have long thought of this as C17th rock music). Much the same in the Gloria, though here there are sections of repose with fragile strings accompanying the solo singers with exquisite beauty. The movement finishes with a kind of joyous jauntiness which I find irresistible. Third movement is a sonata interlude, giving a bit of respite, which opens with what sounds like some fairly archaic instruments. The Credo has some intense solo singing, between more loud stuff from the trumpets and drums. Later there is a wonderful passage with choir singing repeated notes as lower brass dances around below. The Agnus Dei is a satisfying conclusion to the piece, and there are a couple of postludes - a fanfare and a motet. It is a stunning and evocative listen, that can leave you somewhat reeling, in a good way.

Johannes Brahms (1833-97): Serenade no 2 in A (1859).

This piece (along with its predecessor), written when Brahms was in his mid-20s, is probably best-known as a filler on CD sets of Brahms’ symphonies, but it deserves to be known in its own right. It starts freshly lyrical like a glorious spring morning, driven by the winds - the whole piece is substantively a wind serenade with the (lower) strings chipping in; there are no violins (or brass, other than horns, or percussion). The second movement sets off at a real lick, passing the dancing tune around. The third movement, slower but not too slow, has a wonderful depth of expression. The fourth starts with a tentative, smiling, lilting tune, which the harmonies turn into something ardently nostalgic. Then the oboe climbs hesitantly, and finally, confidently has the courage to play a little five-note theme that wistfully and repeatedly rises and falls (I remember those notes as a cue in the double bass part when I played this as a teenager, one of those random memories that stays with you): the whole thing is captivatingly beautiful, one of my favourite movements in all of Brahms. The finale is a joyful, dancing Rondo, again played swiftly here, not milking the moment. Mostly the tune is played by the winds, but the cellos make a couple of gloriously rich contributions. The horns bring touches of grandeur to the proceedings, as it reaches its irrepressible conclusion. I listened to it on the way to work and it was sloshing round my head for the rest of the day.

Anna Clyne (b 1980): The Seamstress (2014).

Clyne is British-born but now lives in New York, and was apparently the most performed living female British composer in the last few years. This is a one-movement sort-of violin concerto, an ‘imaginary one-act ballet’, which starts with a folky low violin solo - vibrato-less and rough round the edges (and apparently built on a tone row, a sometimes forbidding symbol of modernism, but not here). Then the orchestra comes in to expand the expressive breadth. It is mysterious and grieving. A whispered recorded voice comes in, quoting Yeats, and the whole thing gets louder and more dramatic. It then reverts to a more quiet, mysterious mood, like the fog over a Celtic sea. More poetic intoning, which I find very effective. The piece finishes mysteriously and evocatively, with an uncertain wind chord. It is a piece that I hear more in each time I listen to it.

Steve Elcock (b 1957): Festive Overture (1997).

Dramatic fanfares open the piece, then it tries out some catchy themes - shades of Malcolm Arnold, in the way it throws tunes around. A bittersweet theme, almost Elgarian, emerges from beneath, as the winds dance up and down above. The bassoons remind me a bit of Peter and the Wolf. It has a seriousness of purpose about it, regularly slowing and quietening down and sighing. But the slightly rude interjections from the lower brass remind us it’s still a festival. Finishes satisfyingly loudly and with brassy virtuosity.

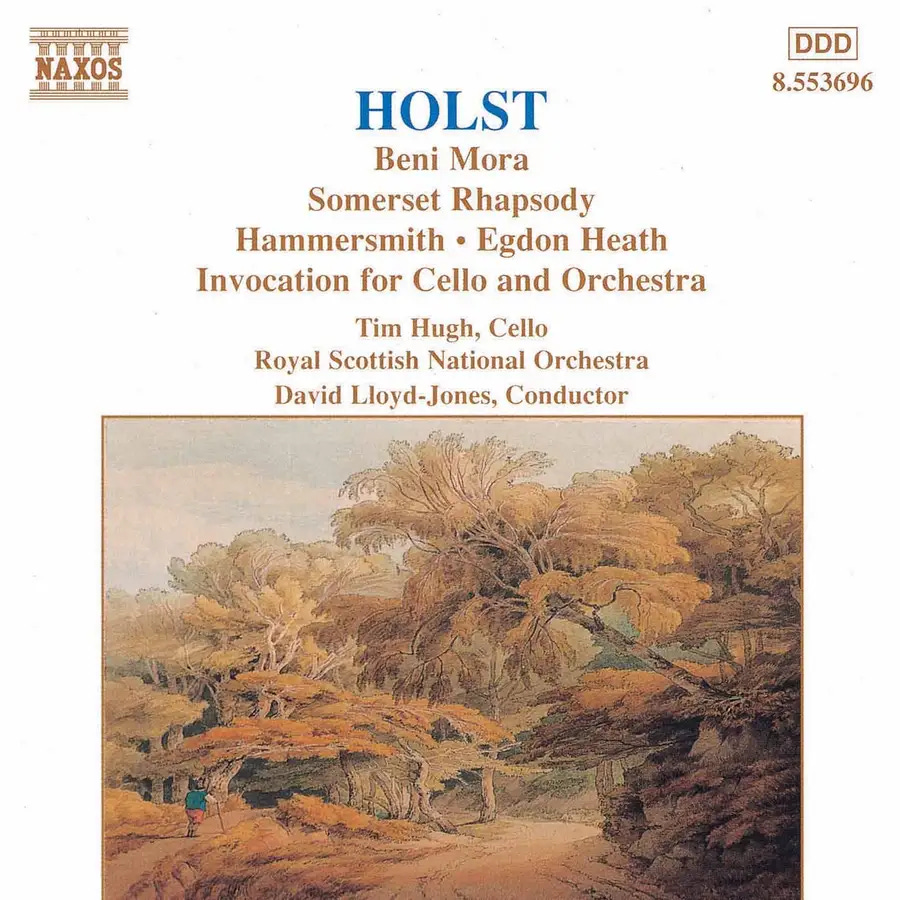

Gustav Holst (1874-1934): Beni Mora (1912).

Holst is mostly known for one piece, The Planets, and although that is wonderful, it has unfairly overshadowed much other great music. He was a great friend of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and in the early years of the C20th they went round England together collecting folksongs. Beni Mora, a three-movement suite dating from 1912 (shortly before The Planets) was inspired by music Holst heard in Algeria. It starts dramatically and assertively in the strings, with a strange, angular tune, which is then taken up by the winds, while the brass tread below. What sounds like a festival arrives from the distance. Later there is an ardent string theme, then horns, then it becomes fragmented and uncertain, with moments of drama: there is a lot packed into this first dance. In the second dance, over rhythmic grumbles, a sad, insistent theme in the winds emerges from the shadows. The movement finishes with bittersweet uncertainty, with pre-echoes of the end of The Planets. The finale, similarly, starts quietly, with a repetitive dance fragment in the flute that struggles to get going, and gradually increases in volume and confidence as other winds join in. The strings join expressively, and another festival arrives, but with that insistent, nagging fragment still audible beneath the increasingly raucous textures. Gradually the music quietens as the festival recedes, but with brief dances occasionally poking out. Timpani take over from the nagging fragment right at the end, and it finishes quietly and uncertainly, unresolved.

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950): Les Bandar-log (1940).

This is part of French composer Koechlin’s longstanding effort to set Kipling’s The Jungle Book to music1. Quiet, strange, slightly harsh orchestral colours create an uneasy atmosphere; an uncertain flute theme; other winds poke out of the texture. Then a brief, chaotic dance, which rattles around. Timpani determinedly end the section. A tune in the double basses (which make several such appearances, always an odd, ghostly sound), then the tubas. It is disconnected, fragmented, edgy, astringent. Various attempts to get a tune going, without much success. Moments of tenderness remind us there is beauty in the world, but mostly it feels angry, and regularly pauses. It has Britten-esque moments - (pre)echoes of the Turn of the Screw. Towards the end it starts to build momentum. A percussion section, with slight echoes of the Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, but with an anguished horn tune above. The brass towards the end is anguished and then just sad. The strings creep up fadingly into desolate nothingness. It is full of incident and I find it compelling.

David Matthews (b 1943): Symphony no 4 (1989-90).

The Symphony starts with a strange, slightly awkward string theme (more echoes of Benjamin Britten, who was a great influence on Matthews), with little interjections. It has an oddly disconnected air, with a weird rising harmonic scale. The third movement is lyrical and strange. A distant horn. The whole thing is unsettling, and impressive. The fourth movement launches energetically with a catchy wind phrase answered rapidly by the strings col legno (played with the wood of the bow). The finale starts slow and sad. When it gets going it has great rhythmic drive, with some really catchy moments. Finishes uncertainly with a rising scale.

Edmund Rubbra (1901-1986): Symphony no 7 (1956-7).

A majestic horn theme opens the piece, and then is joined by the strings, creating a sense of intense momentum. The winds and strings dance in with faster music, but the brass continue to underpin the texture bringing a sense of seriousness. It has a sense of purpose and self-assurance - knows exactly where it is going and what it wants to say. The second movement passes a jaunty theme round the orchestra; there is plenty of incident, little corners of expression and colour. Towards the end of the movement a slow string theme dominates, once more grandly underpinned by the brass, and it finishes with the xylophone joining in grinningly. The third (final) movement starts slow, quiet and intense, with yearning strings, and later the brass dominates, with an funereal mood - somehow it keeps the intensity up for 14 minutes - a solo violin at one point colouring the texture sadly. There are slight hints of Elgar.

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937): Love Songs of Hafiz (1914).

There’s not much to say about this, beyond that it is seductively beautiful, and gorgeously, imaginatively orchestrated. Even fairly early in his career, and heavily influenced by Richard Strauss, Szymanowski, one of the great orchestrators of all time, manages to create a sound world that is utterly distinctive. Each of the eight songs is quite short. The penultimate song has a quiet, rackety drama that reminds me of the opening of the First Violin Concerto, perhaps his most famous work. The final song, comfortably the longest, finishes quietly, sadly and unresolved.

Erkki-Sven Tüür (b 1959): Violin Concerto no 1 (1998).

An angry snort opens the piece, and then the violin plays incessant, agitated arpeggios which gradually quieten before the winds take over. The piece proceeds with alternating types of uneasy - clattering percussion and winds play repeated anxious rhythms, there are various versions of the opening arpeggios, and lots of post-minimalist scratchy hocketing. Halfway through the long first movement the violin tries out some angular lyricism. The accompaniment can’t decide between rich harmonies or angry brass outbursts: there’s so much to catch the ear here, and I find it compelling. The second movement starts very quietly, with low, menacing string chords, before the violin comes and slowly, ardently climbs. The rest of the movement is intensely expressive. Towards the end, echoes of the opening arpeggios sigh out against anguished, industrial chords. The movement finishes quietly and thoughtfully. The finale opens with the violin flickering into life, lots of repeated, quasi-minimalist patterns, and then after a while dances with the accompaniment of tuned percussion. Tension and volume build with screeching brass. A rising dramatic outburst finishes the piece, with a bell left quietly ringing at the end.

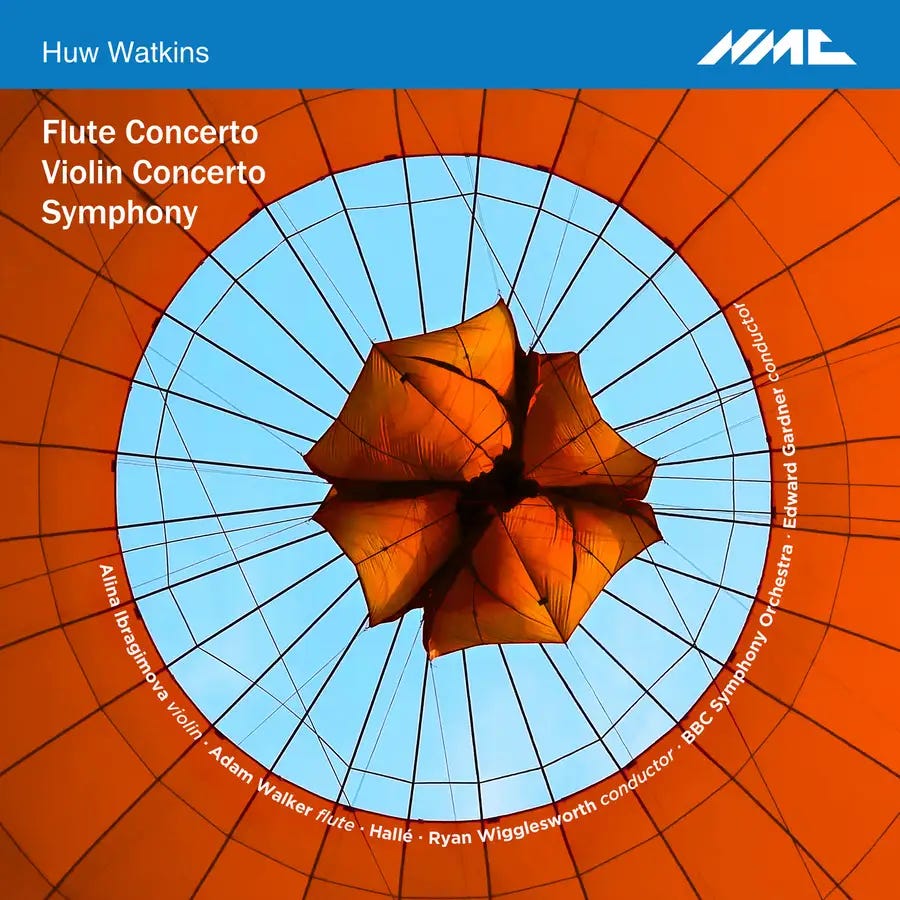

Huw Watkins (b 1976): Symphony no 1 (2016-17).

The piece generates colourful momentum from the off, with galloping winds which seem to have something urgent and important to tell us, mostly quiet, but with occasional rugged, snarling outbursts in the brass. Halfway through the first of its two movements it quietens for a bit, and then gets louder again, the brass more assertive. Evocative, strange fanfares. The movement finishes uncertainly, swaying gently: it has come a long way, but it doesn’t know where it is. The second movement opens with a gorgeous oboe solo over rocking strings. It is tentatively romantic, with yearning winds floating across the landscape rhapsodically, flutteringly. The strings try to make a big tune, and the brass try to assert themselves. As the piece heads towards its conclusion, there is increasing urgency and energy, ideas thrown back and forth between the sections. The piece finishes loudly and dramatically but uncertainly.

Happy listening!

The complete music from the Jungle Book was recorded by David Zinman on RCA in the early 1990s and won a Gramophone Award in 1994, but appears to be no longer available.