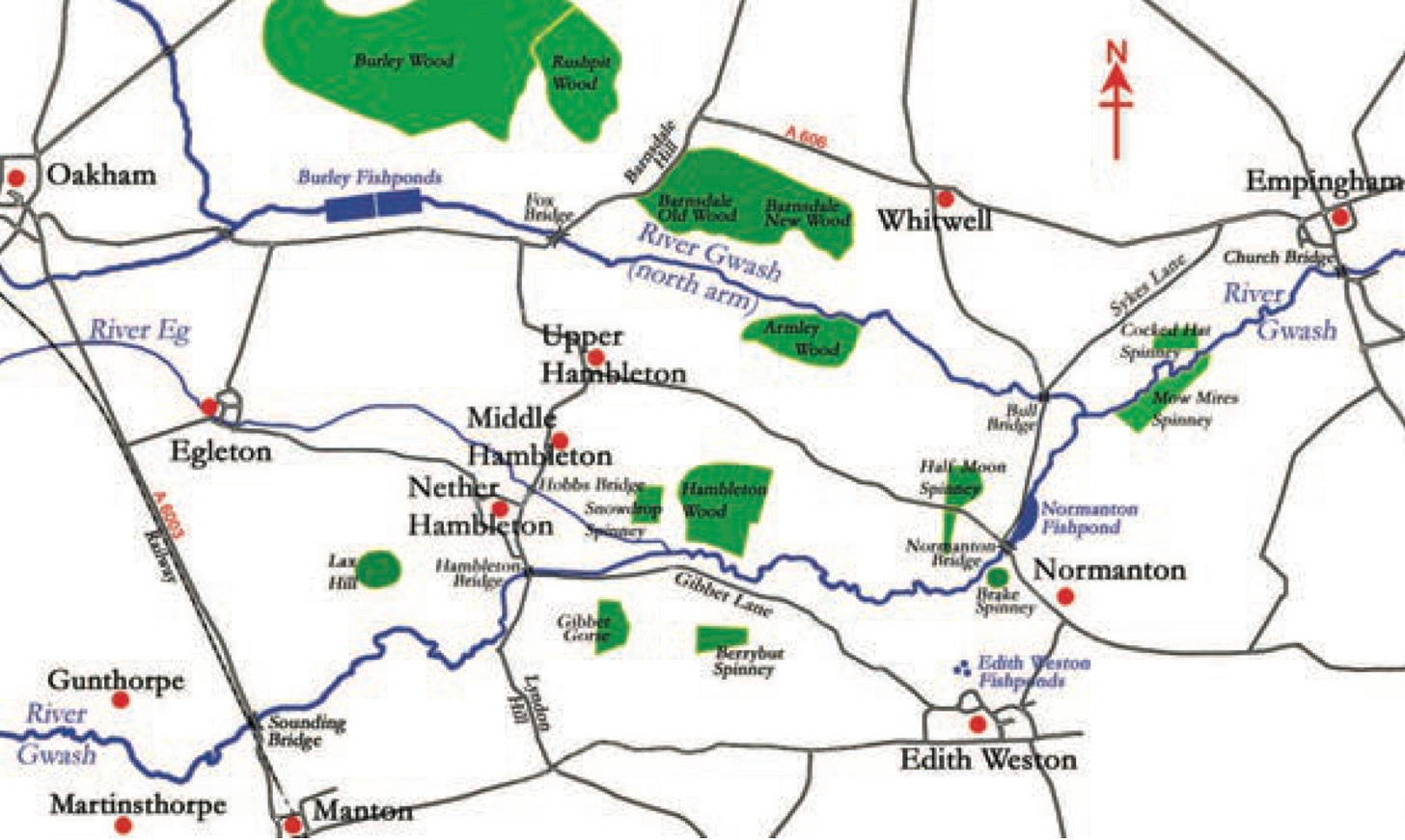

Fifty years ago a large dam was being built at the eastern end of the Gwash valley in Rutland, to create (by surface area) the largest reservoir in the UK. It took three years to flood the valley, and by 1978 the water covered 3,100 acres, fed not only from the Gwash but from the Welland and Nene rivers too. Rutland is famously the smallest county in England, and the reservoir takes up nearly 3% of its land area.

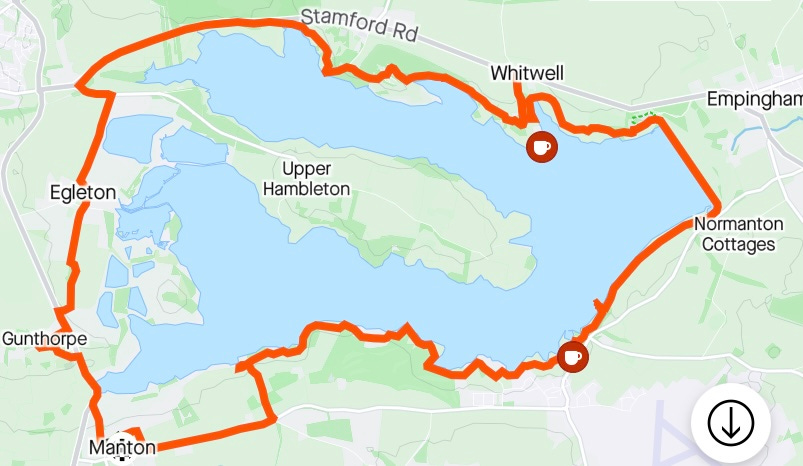

I have twice walked round Rutland Water in the last few years, a distance of about 15 miles. It sounds like a scenic country stroll along the shore, and that’s a good description of the south-east section by Normanton church, which is popular with walkers and cyclists. But not all of the walk is that pleasant: the north-west section involves 1½ miles along a path by the busy, noisy A606, for most of which you cannot even see the water. In the south-west corner, the path by the shore has been closed, and the route goes for a bit along the busy Lyndon Road, which does not even have a pavement. This means the walk overall can feel more a trial than a pleasure.

The route is also not as flat as might be expected for a walk by a lake - the paths on both the north and south shores undulate a lot (on reflection, it’s hardly a surprise that a landscape now flooded to a depth of up to 34 metres is hilly). Manton village, in the south-west corner, is about 30 metres above the water.

And it always feels like a bold commitment to set off round the reservoir. It is not unusual for me to walk fifteen miles, but normally there are options to cut a walk short if the weather gets bad or my legs are feeling weary. Not here: 124 million cubic metres of water block any feasible short cut, so once I’ve gone a certain distance there is no alternative but to carry on. In fact the full walk - which I’ve not (yet) attempted in one go - is about 23 miles, including going round Hambleton peninsula, which juts out from the western end of the reservoir and along most of its length, separating the two Gwash valleys, as if gripped by the water’s right hand.

Nevertheless, I decided to do the circumnavigation for a third time on Friday: I had three villages still to visit to complete the Rutland set, and two of them - Gunthorpe and Whitwell - were near the reservoir. I started at Manton, under which goes the Manton tunnel on the Leicester to Peterborough railway line, joined just south of the tunnel by the line from Corby that comes over the Harringworth viaduct. Almost exactly 100 years ago, on 24 May 1924, five railway workers were tragically killed in an accident at the south end of the tunnel, when fuel oil used for railway lamps exploded.

I decided to go clockwise, to get the section by the A606 out of the way early. Between the road up to Oakham, on the west side of the reservoir, and the water is a nature reserve: 1,000 acres of lagoons and wetlands including the western tips of both valleys, which provide a haven for water birds and other wildlife.

It is here that a ten-metre, 180 million year-old fossil of an ichthyosaur (a marine reptile, the shape of a dolphin) was found three years ago during the routine draining of a lagoon island for re-landscaping. It is the largest and most complete such fossil ever found in Britain.

From the Oakham road I took my detour up to Gunthorpe, a steep footpath away from the reservoir over a level crossing, to discover there is very little there: apparently the village was devastated by the Black Death in the C14th and has not recovered - there are still only a few houses here. Then I set off across fields towards Egleton, with a church I have seen described as an architectural disaster area (though I rather like it), and from there north up the straight Church Road which ends at the road that heads east onto the Hambleton peninsula.

Poignantly there used to be three Hambletons - Upper, Middle and Nether1 - but only Upper Hambleton, the one on the highest land, remains, now with water on three sides. Its neighbours to its south are no longer there, except the Old Hall at the top of Middle Hambleton, and the road that sets off towards them is a dead end. The surviving village has lost the ‘Upper’, now superfluous, and is usually just called Hambleton.

I turned west away from the peninsula, though, and joined the main road from Oakham, which curves back east. After an interlude enduring the roar of the traffic, the footpath eventually diverges from the road and goes south towards the reservoir, then briefly joins the old main road up Barnsdale Hill. The route east from there goes up and down and through woods; I went down to a bird-hide on the shoreline, but saw no birds.

Towards the east end of the north shore is Aqua Park, where lots of boats live. Just north of here is Whitwell, which I went to look at and tick off on my village list - the church here has a double bellcote typical of the area (Manton’s church is similar).

At this point I’d been going 2¼ hours and had walked about eight miles, but decided to press on to the dam at the end of the reservoir, which was originally to be named after the village east of here, Empingham2. Nearby, in 1470, the Battle of Losecote Field was fought, in which Edward IV (elder brother of Richard III, of carpark fame) routed the Earl of Warwick.

The dam itself, 35 metres high and cunningly disguised as a long, unnaturally straight hill with sheep grazing on its landward slopes, heads south-south-east for ¾ of a mile. There is something almost unnerving about such a long, straight, unvarying, unyielding walk, which can make it feel like you’re making no progress at all. But its scale is quietly impressive: a vast piece of land needed to hold back all that water.

When you eventually get to the end, the path turns south-west along what is probably the most popular section of the shore; sheep roam freely here, leaving plentiful evidence on the path. And soon the half-submerged church at Normanton, the symbol of the reservoir and of the county as a whole, comes into view. Originally a parish church (St Matthew’s) and later a private chapel and mausoleum for the Normanton Estate, it dates back many centuries, but the current tower was built in the early C19th, modelled on that at St John’s Smith Square, London.

The church was deconsecrated in 1970 and was due to be demolished to allow the construction of the reservoir - unlike the rest of the village, which escaped the waves, the church’s floor was below the level of the water. But in the end the top part of the church was saved: the bottom half was filled with rubble and a new floor created, and on the outside an embankment was built round it and a short causeway from the shore. When we first went there many years ago it housed the Rutland Water Museum, but it is now used for weddings. In nicer weather than Friday, when reflected by the sun in calm water, it is a magical, slightly surreal sight.

Eleven miles into the walk I wanted a short rest, so went and sat on one of the benches on the far side of the church. The weather was resolutely grey - I did not see the sun all day - and the wind, when it could find me, made its presence felt more than might have been expected for the end of May. The unrelentingly gun-barrel-grey water was choppy and uninviting.

The final stretch of the walk, another five miles westish to complete the south side of the reservoir, was - like the opposite shore - up and down (my phone tells me I climbed a total of over 800 feet during the walk) and partly through woods. But unlike the north side, which is mostly straight, above and slightly aloof from the water, here the path often snakes along the edge of the shore past grazing sheep; in a couple of places there are desire paths short-cutting wide bends of the main track.

At the Lyndon visitor centre the walker now has to make quite a steep climb up a track to the main road, to do the last mile or so back to Manton. My total distance on Friday was a bit over 16 miles, a little longer than normal because of those diversions.

The reservoir feels quite distant on that final stretch towards Manton, and as I paused and looked down on it I could almost imagine what this verdant landscape might have looked like half a century ago, before the waters came and changed almost everything. And I reflected on the quiet strangeness of this place, which keeps me coming back: the dual worlds of a massive and valuable but tightly tamed body of water, and a memory of what was once there, the disrupted normality of the twin valleys, now ghosts beneath. I’ll tread these paths again, I’m sure.

Map taken from http://www.rutlandhistory.org/HRW/FC.pdf.

I live-tweeted a walk from Empingham three years ago. https://x.com/jembenson/status/1401113465729728512?s=61&t=JYO__TLxih2qXHStPjyRPg